Nearly every professional services firm recognizes the market power of thought leadership—the ability to demonstrate superior expertise on an issue. By publishing articles and research reports, delivering conference presentations, and authoring books that lay out a novel diagnosis and solution to a business problem, these firms can generate demand, often even when the economy is lagging.

Whether it’s a consulting service for reengineering business processes or gauging a firm’s emotional intelligence, the professional services firm that achieves thought leadership status becomes a magnet for clients and employees. We’ve seen practices and sometimes whole firms double, triple, or even quintuple their revenue in a few years on the back of a single thought-leading idea.

But while striving to be thought leaders, many professional services firms keep the most important tool for generating thought leadership unused in their toolbox: the case study. In-depth profiles of companies that are leading and lagging on the issue at hand, along with an incisive analysis of what accounts for the differences between the two groups, can provide a goldmine of information for the professional services firm that wants to develop and market a superior approach to solving the issue.

In his 1997 book “The Innovator’s Dilemma,” Clay Christensen used case studies of companies in the disk drive industry to unravel the puzzle of why the best firms in an industry fail. The lesson he derived that “blindly following the maxim that good managers should keep close to their customers can sometimes be a fatal mistake” can be applied to any industry.

Thought Leadership Research Methods: The Limitations of Surveys

Professional services firms conduct hundreds of surveys every year, hoping the data and their analysis will become a strong platform for broadcasting their expertise to the marketplace. Yet most of those surveys yield the marketing equivalent of a one-day run-up in stock price: fleeting press on findings that are soon forgotten.

The reason has to do with the limitations of online and phone-based surveys. Giving respondents multiple-choice answers to a question does not yield the incisive, unbounded information required to shed light on complex business issues. For example, take a consulting firm that wants to attain thought leadership on how to design a successful omnichannel marketing strategy. It could construct a survey asking companies that have built these websites to rank the most important success factors from a predetermined list. It could also ask companies to rate the success of their strategies on a low-high scale.

By comparing the respondents’ responses with high success against the responses with low success, the consultancy could point to issues with a significant gap. If the more successful group of companies listed “top management that champions the effort” as the most important factor and the less successful companies did not have a similar level of top management involvement, one might point to it as a success factor.

But who knows whether it is the most important success factor or whether the survey team missed other factors altogether. And even if it is the most important factor, it’s unclear how the more-successful companies got top management to champion the effort or what that championing looked like. Did it mean top management was involved in designing the new strategy? Removed the roadblocks that surfaced during the initiative? Secured the funding? The answer to the survey question provides only a one-dimensional, superficial answer to a deep, complex question.

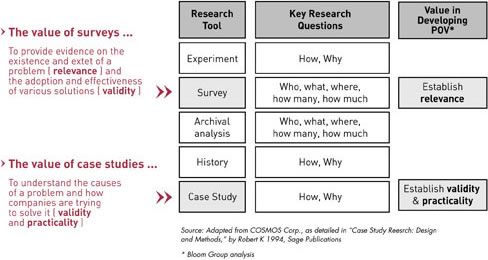

In his book, “Case Study Research: Design and Methods,” Robert K. Yin notes that surveys are the most appropriate research tool for answering “what,” “who,” and “where” questions. “How” and “why” questions—those whose answers attempt to explain a phenomenon—require research tools such as case studies, histories, and experiments.

Using the Right Tools to Develop Intellectual Capital

For professional services firms, understanding what works in the field and how it works is critical to developing new approaches. “I have closely studied the inner workings of boards,” Ram Charan, one of the leading thinkers on corporate governance, wrote in his book, Boards That Deliver.”I haven’t performed quantitative or statistical correlations between corporate performance and variables of corporate governance. Frankly, such research doesn’t get to the causality of what leads to good governance. Rather, I have focused on what happens behind the curtain, so to speak, inside the boardroom.”

Case study research is a research tool to get behind the curtain on any business issue and shed new light on it. It is vital for creating the prescription and providing proof that your recommendations work. It was case study research that we conducted with Deloitte Consulting on business model innovation that uncovered novel findings about companies whose radically different business models enabled them to build huge businesses in markets others considered undesirable. Deloitte’s insights on this issue led to a cover article, Bottom-Feeding for Blockbuster Businesses, in the Harvard Business Review. Not only does it break new ground, but case examples also resonate with a professional services firm’s target audience, who love to hear war stories.

Conducting Case Research: The Process

When case study research works well, it provides insights into how organizations addressed a certain issue. The case study reviewers’ analysis of how these firms resolved the issue—identifying patterns in approaches that were or weren’t effective—provides the content for the prescriptive half of the point of view. A point of view from a professional services firm that merely identifies an issue or problem—which survey research is best designed to do—is only half a point of view. It cannot generate thought leadership because the most important part of its thinking is missing — the prescriptions that demonstrate the professional services firm knows how to resolve the issue.

To generate big insights from case studies, you need to study how a sufficient number of organizations have addressed the issue. Ideally, two kinds of organizations: those that have resolved the issue and those who have struggled or failed. Jim Collins, author of “Built to Last” and “Good to Great,” compares a set of best-practice companies against a control group. Explaining his research approach on his website, Collins says: “The cornerstone of our research method is the selection of a credible study set, the direct comparison of that set to a carefully selected control set, and the study of the contrasts between each set over a long period of time.”

Without a control group, it’s difficult to understand what made the difference among best-practice examples. For example, going back to the omnichannel marketing strategy topic, a consulting firm that wanted to become a thought leader and develop a new service in this area would need to secure interviews with several companies in both camps. How many? In our experience, 10 best practice and 10 bad-practice companies would be the minimum. The greater the number of companies comprising the research base, the richer the data upon which to identify patterns, and the greater the chances for seeing patterns that no one has previously uncovered.

The Case Study Research Process

We often hear from professional services firms that dozens of case study examples are unnecessary. Their chief concern is the time and resources to secure, conduct, and analyze them—all of which can indeed be significant. And yet, we also hear of the necessity for thought leadership on an issue to differentiate themselves and gain clients.

Ultimately, the power of ideas that emerge from case study research will only be as good as the resources devoted to it, the number of cases done, and the creative and analytic power of the analysts who try to divine the patterns. There are no shortcuts to generating strong ideas. If there were, 99 percent of the business books published would be bestsellers.

There’s another way to look at the resources issue. The less case material there is to draw upon, the more the analysis must rely on trying to weave a powerful message from sparse and inconclusive data. Much like trying to draw a detailed connect-the-dots picture with only a handful of dots, finding never-before-seen patterns about the true roots of a problem and how to solve it won’t be easy.

The analysis that results from such sparse case study data typically breaks no new ground. Lacking sufficient data for seeing patterns, the people doing the analysis are forced to bring a preconceived idea to the table and selectively use the part of the data that confirms it. And those preconceived ideas are almost always derivatives of others they’ve already read elsewhere.

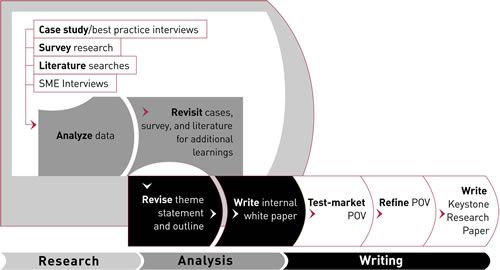

When conducting case study research, we begin by selecting at least 10 organizations to study on a particular business topic. Then we create a questionnaire to guide the interviews based on three to five of the research team’s original hypotheses on the topic. Without these hypotheses, the search for information can be too broad. At the same time, the research team must be ready to quickly throw out hypotheses that the data invalidates.

Next, we set up three to seven interviews with those within an organization to get a full picture of the issue. After conducting all the interviews at each organization, our interviewers write up what they heard, presenting the first level of analysis for the point of view.

After all these case study reports are written, our analysts—working in concert with our client—read all the case study reports and brainstorm about the differences between best and bad practices. If the case study reports are truly incisive, they will provide rich material upon which to do the second level of analysis, which can require several full-day working sessions involving a team of no more than six people with expertise in disciplines related to the topic. Sometimes, the biggest patterns in the data do not emerge until the last workshop. But when they do, the novel approach to solving the issue emerges. As the team goes back to the case study data and weaves the findings through it, the framework gets stronger.

Looking Back to Go Forward

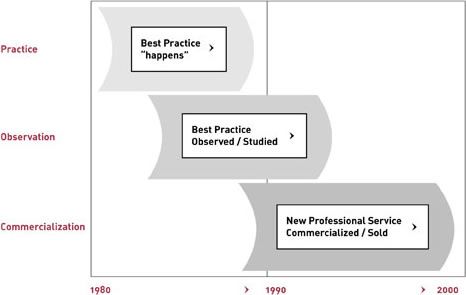

When we explain to professional services firms the critical role of case studies in thought leadership, they often reject this approach, calling case studies ancient history. “We need something new,” they say. Exactly. That’s the irony of case studies. One of the best ways to develop new insights and service offerings is to look at the experience of companies that have already solved the issue, much like Michael Hammer did by comparing best and bad practice companies on how they were using IT to improve operations in the early 1980s. “I didn’t invent business reengineering. I discovered it,” Hammer told a reporter. More than 10 years passed from the time the best-practice companies were doing their thing and when a consulting firm identified and packaged it into a service.

The Commercialization of Business Analytics

The same timeline plays out for each big consulting concept. Take business analytics, a concept created by Tom Davenport in 2005 from observations of how business intelligence applications were being used at 32 companies, including Harrah’s, Capital One, Best Buy, and Novartis. Davenport and his team interviewed two to four managers at each company and then spent three months analyzing the results before publishing “Competing on Analytics” in the Harvard Business Review in January 2006. By that time, companies had already been deriving knowledge from electronic data for years. But since the article was published, business analytics became a sizeable industry in its own right.

Making the Case for Case Research

Professional services firms spend huge amounts of money on developing and marketing new ideas. They realize that generating strong demand for their services requires demonstrating insights that their competitors don’t have. But the development of ideas that are a big departure from the pack is a still-rare occurrence. Those that put case study research at the center of their intellectual capital development have a much greater chance of uncovering true thought leadership.