White papers have long been a staple of business marketing, especially in industries that sell complex offerings. Even amid the rise of digital marketing and social media, white papers retain a prominent place in the marketing mix. Corporate websites are filled with white papers; lead generation campaigns endlessly offer them in exchange for contact information; and a vibrant ecosystem of research firms, custom publishers, content syndicators, specialized writers, and even training and consulting firms has sprung to life over the last several decades to feed the white paper beast.

At their best, white papers can quickly open doors with senior executives and spawn opportunities to solve customer problems. However, few white papers generate much interest. Most are forgotten as soon as they are published or languish unread in dusty corners of corporate websites. Salespeople often ignore them, or, if they hand them out, customers don’t read them.

A recent study of IT buyers found that only 7% definitively see white papers as trustworthy. Another study found that two-thirds of IT buyers are disappointed with the quality of white papers, a higher percentage than for any other type of marketing collateral. A third survey found that the print and online articles of more than 100 consulting firms are only moderately effective at generating leads and creating market awareness of their services.

Do White Papers Still Matter?

For some advocates of online marketing, such criticisms of white papers mean that newer thought leadership marketing channels should rise to the fore — webinars, e-books, video, blogs, Twitter, and business networking websites like LinkedIn. At the far end of this spectrum, we’ve even seen debates about whether blogs and other “long-form” writing are necessary for thought leadership at all when experts can Tweet their advice in 140 character chunks.

These arguments are misguided. While many white papers should never have been published, that doesn’t negate the medium’s potential. In fact, white papers remain one of the best thought leadership tools marketers have. But only if they have compelling points of view. More than 800 buyers of business services polled by the Economist Intelligence Unit ranked white papers third in a long list of ways they wanted to be marketed to, far ahead of telesales, print advertising, and in-person sales calls.

While other marketing channels can be valuable, the real issue is producing content that presents a novel point of view on how to address an important market problem, backed by substantial and credible evidence. For this, white papers have two important advantages over most other marketing formats:

- Putting in writing a cogent, well-developed argument based on weighty evidence is a great way to force clear thinking, resolve internal debate, and move marketing and sales in the same direction on an important topic.

- Putting the entire argument in one place for customers and market influencers to read can demonstrate the rigor of research, analysis, body of evidence, and the totality of the argument –the full examination of the problem at hand and the solution.

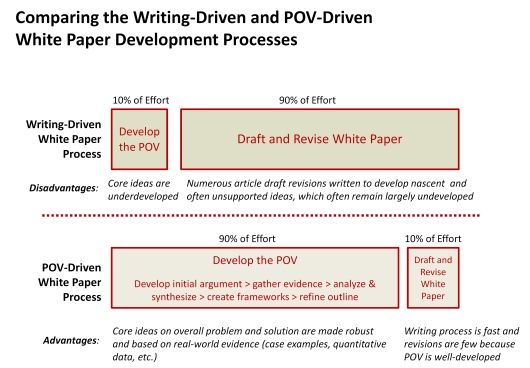

Unfortunately, few white papers capitalize on these inherent advantages. Their fatal flaw is that they are treated as writing projects, not as structured initiatives to develop a compelling point of view. Their emphasis is on phrasing an argument, not on building it.

From our experience, white papers that open doors, generate substantial prospect inquiries, and get the press, analysts, and other influencers to quote them are created very differently. The majority of the time producing them is devoted to creating a powerful argument based on real examples and other evidence. The writing process itself is relatively short when a strong point of view has been developed in great detail.

In this installment, we examine the process of content development for several white papers that have yielded substantial market interest and leads. We draw on two examples: Quantum Performance Inc., a small strategy consulting firm, and Unisys, a large IT services company. Each created white papers that generated substantial market interest in their services.

It’s More Than a Writing Problem

Most white papers are viewed as writing projects: Assign a staff person or hire an outside writer, pull together some background material on the topic at hand, arrange a few discussions with a subject matter expert, set up a few customer interviews, and then draft the paper. Several drafts later, add some graphics, make sure it all reads okay, and then publish. Modest white papers may take a few weeks or months to produce in this fashion; more substantial ones can take six months or even longer. Either way, the bulk of the energy is spent on explaining the ideas – writing, reviewing drafts, revising, and editing them – not on how to develop and substantiate them.

Many white paper “experts” counsel even more attention to the writing process. That sounds like good advice. Who doesn’t want good writing? However, the best white papers generate attention, conversation, and leads based on the power of the point of view, not on the quality of the writing. They provide uncommon insights into a problem and how to solve it, creating order out of chaos. The problem with the writing-centered approach is that the underlying point of view is typically underdeveloped.

Five Steps to a Compelling Point of View

A strong and distinct point of view is not likely to result from a process that tries to put ideas in prose and uses article revisions to sharpen the thinking. Rather, a powerful POV is far more likely to happen when the prose-writing is saved for the end of the process. In fact, in the first five steps, no writing of prose should occur at all:

- Develop the initial argument

- Gather the evidence

- Analyze and synthesize

- Create the core frameworks

- Craft and refine the outline

1. Develop the initial argument.

A compelling point of view deeply explores an issue and the optimal solution to it. Too many white papers wrongly focus on one or the other. Some focus on the problem, presumably to demonstrate knowledge of an industry, functional or other business issues. White papers that focus on the solution can lack relevance: Readers may not adequately understand the issue on which a paper is trying to shed light. Still, others cover both problem and solution but state the problem unclearly, leaving readers to wonder exactly what issue of theirs the paper is addressing.

The best way we have found to launch a white paper project is to create an initial version of the overall argument – problem and solution. This storyline is likely to change throughout the process as evidence is gathered. But it helps to sketch out the argument clearly at the beginning with answers to the following questions:

- Target problem: What is the specific problem in the world that the authors are addressing? Who has the problem (what kinds of companies, and what executives in those companies)? How would those people express the problem (rather than how would the authors express it)?

- Shortcomings of current solutions: What are the existing approaches to solving the problem, and why are they falling short? Showing familiarity with other approaches to solving the problem builds reader buy-in that you do, in fact, have a grasp of their issue.

- New solution (overview): At a high level, what are the authors saying must be done to solve the problem?

- New solution (dissected): At a detailed level, what is the solution? The components, elements, and steps to solving the problem?

- Barriers to adopting the new solution and how to overcome them: What might stand in the way for the reader who wants to explore the solution? What organizational hurdles should he expect to face? While this may appear to discourage readers from adopting the solution, it will encourage them if done well. They will gain confidence in a company that understands where the roadblocks are to adopting its offering – and much trust if it shows how to remove those roadblocks based on real examples.

- Call to action: Explain why the reader shouldn’t hesitate to solve the problem in the prescribed manner.

The answers to the questions above will form the initial argument. This should be put in a high-level outline – 10-20 bullet points at most, explaining each point. After putting it into this form, the authors should identify and scan other views published on the topic to ensure they don’t create the same message.

This was a critical early step for Quantum Performance Inc. in developing a white paper that has helped power up its lead stream. In 2005, the strategy consulting firm, which specializes in organizational alignment and engagement, set out to create a white paper on its approach to creating “strategic commitment.” Before the white paper, Quantum had difficulty generating leads beyond word-of-mouth references. Though Quantum had lots of client success stories to point to, prospects didn’t fully understand the firm’s consulting process, which helps an executive team create a strategy that employees at all levels embrace. In developing a white paper to market their services, Quantum went through a painstaking effort to answer these six questions. Also, to ensure their approach would be novel, they compared their initial argument to what other consultants had written on the topic. They read through 10 years of Harvard Business Review articles on organizational change. That helped them to avoid covering familiar ground.

Creating the initial storyline by answering these six questions serves another purpose: Only when the argument is laid out in such a manner can the authors determine what parts of their point of view are missing or need further development. Developing those parts is the next step in the process.

2. Gather the evidence.

The high-level outline will quickly show the holes in the argument: problem statements that may need further evidence to prove the problem is real or pervasive; solution statements that need to be illustrated through examples of companies that have adopted the prescriptions; other company examples showing the financial benefits of “the cure.” Without such concrete evidence, executives will view a white paper as theoretical and its prescriptions risky. These papers end up in the trash.

Several surveys have shown that what managers value most in white papers is learning how other companies solve problems. This is a critical element of Harvard Business Review’s success: Few publications do a better job of laying out examples of companies with innovative management approaches.

The evidence necessary to make a white paper compelling takes three forms:

- Primary quantitative data: Surveys can help validate the existence and contours of a problem: how many companies are dealing with it, what executives consider the most important aspects, the challenges and benefits of different approaches, and so on.

- Primary qualitative data: In-depth case studies are critical to digging deeper into how companies have addressed the problem in the past and how they have solved it. Case studies provide the texture that brings complex business issues to life.

- Secondary data: The Internet and search engines have made it easy to gather lots of supporting evidence for a point of view and identify potential case studies. Today an abundance of executive presentations and transcripts from investor conference calls can be found online. Many yield nuggets of revealing information on company strategies.

Of the three, primary qualitative research is the most critical data to collect. Executives need proof that other companies have solved a pressing business problem in the manner prescribed in a white paper. In developing its white paper on strategic commitment, Quantum drew on more than a dozen client engagements. Similarly, Unisys Corp., a $5 billion IT services firm, wanted to demonstrate its expertise on the topic of how to provide technology support in a large organization, one of its core outsourcing services. In 2005 the company conducted a major survey on the tech support practices of 200+ U.S. companies. It found that those with the best tech support did not take the typical “VIP approach” – i.e., senior executives getting the best IT service in a company. In fact, the workers at all levels who generated revenue every day (sales, field service, customer support, etc.) and who depended on online information got the most tech support. The company also conducted case studies on 10 organizations (including clients) to offer concrete examples of how such tech support approaches were critical. The research was used in a highly successful marketing program that opened doors to tens of millions of dollars in new outsourcing opportunities.

To be sure, some white paper budgets may not allow extensive research. But it is not always necessary. Companies with significant experience or research on an issue have content that their marketers can tap for a white paper. At the same time, secondary research can yield useful data to support a new point of view.

Yet secondary research has its limitations. Using articles with company mentions to write case studies is fraught with risk: that the articles are wrong or that there is insufficient data to write a rich case example. To present compelling examples of companies as proof of one’s point of view, there is no substitute for talking directly to the executives of those companies and learning “how they did it.” If a company depends on a white paper to open doors but lacks evidence that its solution works, it must gather that evidence. In this case, nothing short of a case study will suffice.

3. Analyze and synthesize.

With data in hand, marketers must commit time to figuring out what it all means. This is an iterative process that should involve several people knowledgeable about the issue of the white paper. First passes at research rarely tease out what is most significant, and collective thinking is almost always better than that of an individual.

One of the best places to start analyzing data is to compare companies that solved a given issue well against other companies that addressed it poorly. The more data one has of “leaders” and “laggards” on a specific business issue, the better this analysis becomes. In its white paper on tech support practices, Unisys compared survey respondents with the best technical support to the companies reporting the worst tech support. It was here that Unisys found companies with the best tech support were far more likely to give high levels of service to employees whose jobs affected revenue every day and needed technology working every minute.

Truly new insight will only emerge with a rigorous process of analysis and synthesis. The analysis involves studying and mining the data, looking for patterns and important findings. Analysts often sort and cluster the data in various ways to help uncover what is most significant. Synthesis then involves refining, combining, and integrating the key findings into new insights—then checking those with other experts to assess their validity and importance.

4. Create the core frameworks

At the heart of any compelling point of view lie one or more frameworks that help executives diagnose a complex challenge and determine how to address it. These frameworks give readers a structured way to think about the issue. Frameworks are an essential outcome of synthesis; without them it is difficult to provide generally applicable advice.

Good frameworks are not easy to develop. But they can help your white papers stand apart from the crowd and demonstrate true insight into important business challenges. Too many white papers lack effective frameworks. Thus, they don’t provide memorable ways for the audience to continue to dissect their issues after reading a white paper.

Frameworks cover a spectrum of sophistication and usefulness. At their simplest, they are purely descriptive. They don’t directly shed light on some problem in the world and how to solve it. They merely describe the state of something, such as the declining share of American cars in the U.S. auto market, the increasing share of discounters in the U.S. retailing industry, or the market shares of ERP software vendors.

The most powerful frameworks are diagnostic or prescriptive. They help buyers better understand and solve the problem. The classic SWOT framework is a good example of a diagnostic framework. It provides a simple, useful structure to help business people understand their company’s competitive situation without saying anything about what a company should actually do.

Quantum Performance’s diagnostic and prescriptive frameworks included its two core elements of creating and executing a strategy: the content of the plan and its context. That framework showed how an executive team could assess content and context to determine how well a strategy would be adopted. For its white paper on technology support, Unisys developed six core prescriptions.

Quantum Performance’s diagnostic and prescriptive frameworks included its two core elements of creating and executing a strategy: the content of the plan and its context. That framework showed how an executive team could assess content and context to determine how well a strategy would be adopted. For its white paper on technology support, Unisys developed six core prescriptions.

Frameworks that are both diagnostic and prescriptive help executives better understand their situation and what they should do about it. The Boston Consulting Group’s growth-share matrix is a good example of this type of framework. It enabled business units to be classified according to market share and growth rate and then prescribes a strategy based on the outcome.

However, good diagnostic and prescriptive frameworks are hard to develop. Although the BCG matrix was once used widely, it has gradually become overly simplistic and has been replaced by more comprehensive models. Most white papers will have separate frameworks for diagnosis and prescription.

A white paper with clear, credible, and engaging frameworks is a powerful tool for shaping buyers’ thinking. The best frameworks have long shelf lives and support marketing and business development far beyond the typical life of a single white paper.

5. Craft and refine the white paper outline

Once the framework is in place, the next step is to refine the overall argument: a clear articulation of the business problem and how to solve it. The best way to do this, in our experience, is to create and collaboratively refine a detailed outline.

White paper writers often jump right into a first draft of the paper itself, perhaps based on a high-level outline of what they want to include. The problem with this is the lack of collective refinement of the argument. Moving too quickly into the drafting stage increases the risk that you won’t get it just right, and the project bogs down into a communal debate about wording and editing. We’ve seen conventional white papers drag on for months as the writer presents draft after draft that pleases no one.

By focusing first on the outline, you can get the argument right before starting to draft. The outline should be detailed, including the high-level points and the specific data and proof points to support the argument, along with any frameworks, sidebars, and other supporting material. It’s fine if the outline is longer than the paper itself. Including all the details minimizes the chance of fundamental problems with the argument set forth in the draft.

It may well take half a dozen or more iterations of the outline to get it right so that everyone is comfortable with the argument and supporting material. But this is a critical step, and it is much more easily done with an outline than with narrative text since the outline is all about the argument, not the final wording. Once the outline is set, the drafting itself comes quickly; a very good first draft should take only a few days. Because there should be no debate about the argument, moving from the first draft to the final text should also come more quickly since it is just a polishing process rather than another round of haggling over the storyline.

It’s Power of the Point of View, Not the Power of the Pen

White papers that grab executive attention must make new and compelling arguments, ones supported by illuminating examples of companies that have adopted the prescriptions set forth in the paper. Such arguments don’t typically emerge when the task of writing is driving the process. When most of the process is consumed with writing and revising draft copy, a company should expect the core ideas in those drafts to lack novelty, evidence, and rigor. They should expect a tepid market reaction when they put those ideas in the market.

Instead, companies that need white papers to generate market interest should devote most of the white paper process to developing a strong point of view. When they do, they will spend most of their time collecting evidence on the problem and how to solve it and refining their core argument. The copy will take far less time to write, and it will be far more persuasive.

Yet, that copy is not the final step in the process. Possessing new, powerful content, a company has the opportunity to take it to market through numerous marketing channels. Quantum, Unisys, and others brought the points of view they published in their white papers to market in numerous forms including client briefings, article submissions to third-party publications, conference presentations, and more. Companies that want to greatly increase their white papers’ impact shouldn’t limit themselves to just publishing a white paper.

Yet, that copy is not the final step in the process. Possessing new, powerful content, a company has the opportunity to take it to market through numerous marketing channels. Quantum, Unisys, and others brought the points of view they published in their white papers to market in numerous forms including client briefings, article submissions to third-party publications, conference presentations, and more. Companies that want to greatly increase their white papers’ impact shouldn’t limit themselves to just publishing a white paper.